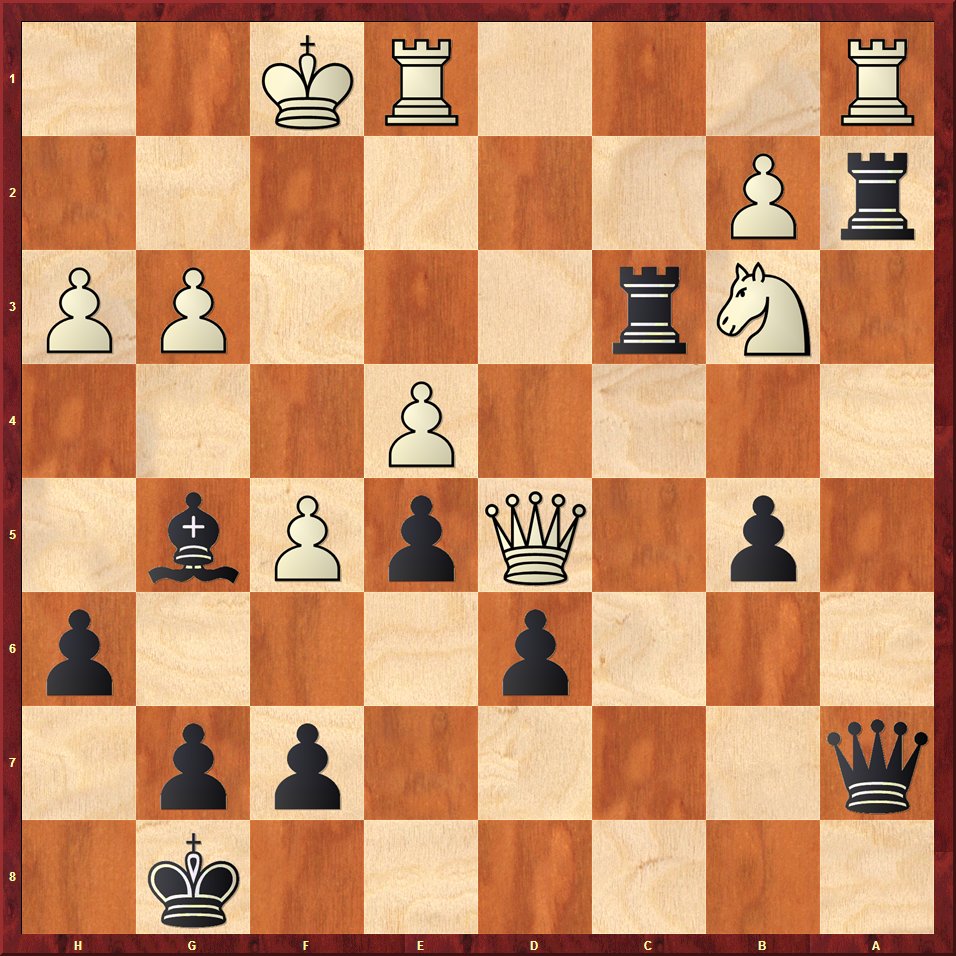

Core Evaluation

1. How has the opponent’s last move changed the position? Has your opponent made a blunder?

2. What is he trying to achieve?

3. Has he weakened his position (positional concession, piece en prise, open to a tactic) ?

4. Are there any threats?

Tactical Evaluation

If 1 or more of the following exist, then perform a tactical evaluation if none exist proceed to the Positional Evaluation section:

1. Loose (unguarded) pieces : Loose pieces drop off LDPO

2. Weak back rank

3. Pieces that can be easily attacked by enemy pieces of lesser value

4. Pieces that can be attacked via discovery

5. Pinned or skewerable pieces along the same rank, file or diagonal

6. Pieces (or squares) vulnerable to knight forks

7. Overworked pieces (pieces guarding more than one piece or square)

8. Inadequately guarded pieces

9. Falling way behind in development

10. uncastled King or lost pawn protection with Queens on the board

11. Open enemy lines for Rooks, Queens and bishops to your King

12. Pieces that have little mobility and might easily be trapped if attacked

13. A large domination of one side’s forces in one area of the board

14. Advanced passed pawns

Positional Evaluation

1. What is the material balance?

2. Are there any direct threats?

3. How is the safety of both Kings?

4. Pawn structure questions:

a. Where are the open lines and diagonals?

b. Are there any strong squares?

c. Who is controlling the center?

d. Who has more space and where on the board do they have it?

5. Which pieces are active and which are not?

a. Are there any weaknesses in my position?

b. Are there any weaknesses in my opponent’s position?

c. Are there any strengths in my opponent’s position?

d. What are the strengths in my position?

e. Which is my weakest placed piece? How can I improve it?

Candidate Move Selection

1. based on above select 2-4 candidates

2. Begin analyzing the most forcing candidate first

NOTE: When analyzing look for opponent’s best response and look 2 1/2 moves (5 ply ahead).

If there is a combination, then you need to calculate until quiesence.

3. Double check that at the end of your analysis your opponent doesn’t have a killer move (deadly in-between move or tactic)

4. Evaluate the position at the end of your analysis:

Even, W / B is slightly better, W / B is better, W/B is winning, unclear

5. Rank your candidate move based on evaluation.

6. Depending on time constraints and the quality of your recently analyzed candidate move go to step 2.

a. if your candidate’s analysis weakens your position (leaves you better when winning or even when slightly better, then analyze the next candidate on your list)

b. If your candidate leaves you in the same position (even when even, winning when winning), then decide whether you want to take additional time to analyze the next candidate on your list. The next candidate might take you from even to winning, so even if you found a good move, look for a better one if time allows.

Blunder Check

7. Write down your move.

8. Perform a blunder check

a. are you leaving a piece en prise?

b. Are you missing a killer tactic?

c. Are you missing a killer in-between move?

d. Are you positionally weakening your position?

9. PLAY the move