I have made an observation while solving puzzles, that I feel will improve my tactical puzzle solving skills, and might have direct application during actual games.

When solving a tactical puzzle of intermediate to advanced level I either:

1. Have no clue how to go about solving it and get it wrong.

2. Have multiple ideas that look promising, but after further analysis don’t win {usually end up playing one of the two and get the answer wrong}.

3. Solve the puzzle correctly.

This post is going to focus on solving the 2nd category above. I have found that you will get many more puzzles correct by combining ideas that arise by analyzing different candidate moves. Unfortunately, by not making a link between the two, or forgetting about your first idea when looking at the second, I mainly fail to connect the dots and only after reviewing the correct answer do I see that I had been on the right track and would have answered correctly if I had combined my candidates.

You might want to solve this puzzles on your own before reading the answers below taking into account your thought process while doing so and then see if you encountered the same issues as I did.

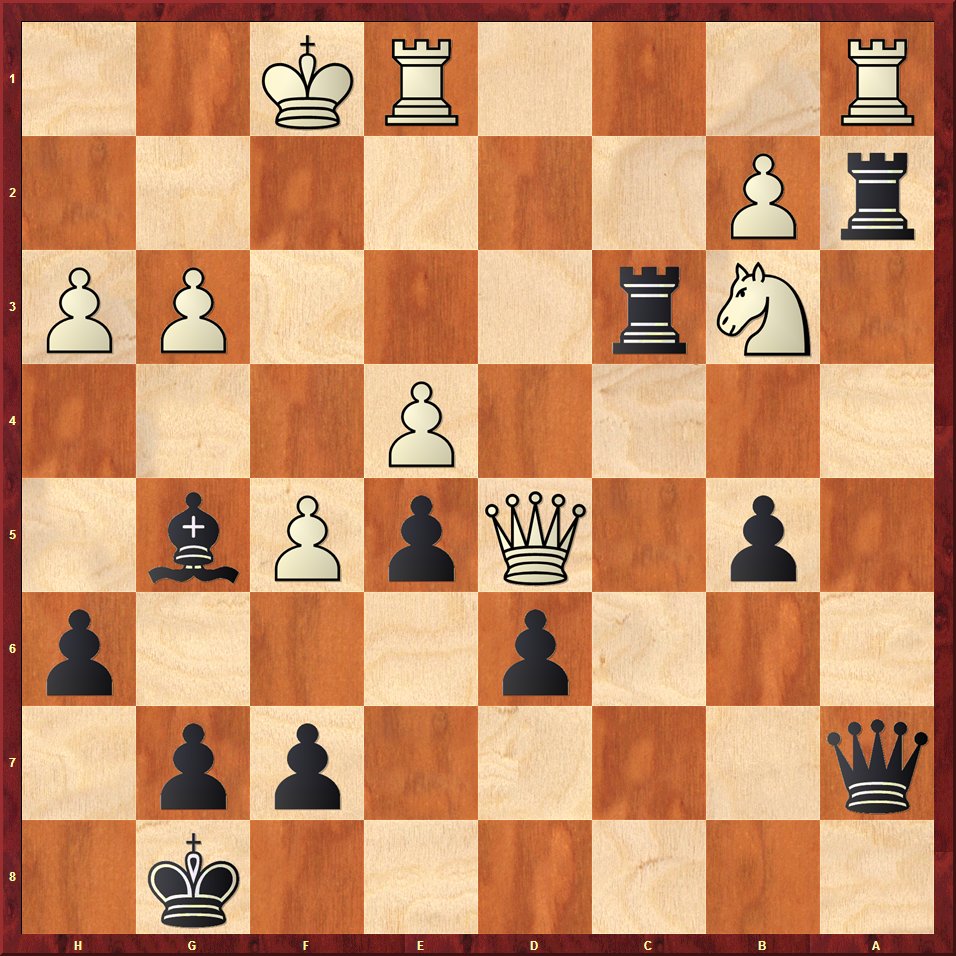

Here’s the first position we will look at:

White to move and win

The first candidate that came to mind was 1.Bb6 attacking the Queen. I analyzed the response 1…Nxb6 2.axb6 Qxb6 which loses a pawn for White and the Black Queen lives on. So I abandoned this candidate and looked for a better move.

I then found that Qh6 looked promising and I began to analyze 1.Bh5 with the idea of Bh8 and then getting my Queen to h6. But I soon found that 1.Bh5 was a slow since it allows 1…Kh7 and White is out of gas. What I missed, and where I think there is room for improvement, is if I would have combined both moves. Attacking the Black Queen with 1.Bb6 with the idea of freeing the diagonal for my Queen to get to h6 with mate was the winning combination and one I failed to see by not connecting the dots.

Let’s look at another example, and one which occurred right after I had attempted to solve example #1 above.

White to move and win

In this position quickly saw that both the White rook and Queen were attacking the Black d8 rook, and that there might be a tactical opportunity if the Queen were deflected from its defense. The candidate that came to mind was 1. b4 but after further analysis I saw that the Queen could seek shelter by moving to 1…Qc7. The other candidate that stood out was 1.Qf6+ but the King can easily get out of the way with 1…Kg8 and there aren’t enough White pieces in the vicinity to force the issue. The third candidate I analyzed was attacking the undefended bishop with 1.Qe7 but I found that the bishop can get out of harms way via 1…Bc8. If I would have combined the two ideas or even looked a few ply deeper I would have found the answer 1.Qe7 attacking the bishop and preventing the Queen from seeking shelter at c7 after deflecting her with b4. 1…Bc8 2.b4! and Black resigned.

).

).